Mary Birkett Card (1774-1817)

By Josephine Teakle

Biography

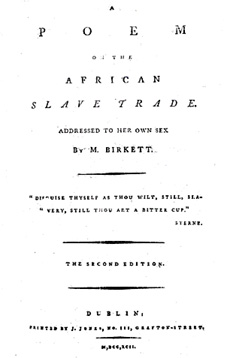

In 1792, Mary Birkett, a Dublin Quaker, published A Poem on the African Slave Trade. Addressed to her own Sex. in two parts. The poem is noteworthy for the way in which it urges other women to boycott slave produced goods (sugar and rum) in protest against slavery. In this it may be unique as it is the only poem historian Clare Midgley 'identified', in her study Women Against Slavery, 'which was written by a woman and directed specifically at her own sex' (p.34). Until lately nothing was known about Mary Birkett's life. However, her son, Nathaniel Card, made an extensive manuscript collection of her writings in 1834, and this was kept within the family. I recently edited this collection, recovering Mary's life from the writings, Quaker archives and other sources.Mary Birkett was born in Liverpool, the eldest of thirteen children born to William Birkett, a soap boiler and tallow chandler, and his wife Sarah, née Harrison, the daughter of a Kendal shoemaker. In 1784 the family moved to Dublin, joining other relatives already in business there. Tragically, nine of Mary's siblings died in childhood. Three succumbed, probably to scarlet fever, in March 1787, with Mary poignantly expressing her grief in a short poem on each death. There is no record of Mary's education, but her childhood poems show her to have been well read. A Poem on the African Slave Trade, written when she was only seventeen, is full of classical allusion.

It is likely that some of her enthusiasm for the anti-slavery cause derived from the involvement of her uncle: her mother's brother George Harrison. He had become a wealthy merchant and banker in London, influential in the Society of Friends, or Quakers. His wife Susannah was the daughter of William Cookworthy of Plymouth, the Quaker chemist who discovered china clay, thus establishing the English porcelain industry. Harrison was one of six Quakers who set up the first association in England to work against the slave trade in 1783. In 1787 this group joined with Thomas Clarkson and others to form the London Abolition Committee, the main organisation that worked with William Wilberforce to abolish the trade. That year, Harrison was one of eight members on the sub-group that created the seal used as the template for Josiah Wedgwood's famous medallion, featuring a kneeling African in chains holding up his hands in supplication with the words 'Am I Not a Man and A Brother?' (Jennings, p.39). This design became a distinctive emblem in the campaign, featured on jewellery and other items used or worn to denote support for abolition. Harrison worked devotedly for the cause for most of his life, continuing as an active member of the Committee right up to the final meeting for which minutes exist in 1819 (Jennings, p.122). Mary's family maintained close links with the Harrisons. She stayed with them in London in 1794, forging a friendship with George's daughter, Lydia.

Mary's poem was written at a particular juncture in the abolition campaign. Publication of Parts I and II may have coincided with the passage of the 1792 Abolition Bill through the House of Commons in April and the Lords in May/June – Part II contains an address to members of the House of Lords. At this point, George Harrison published an Address to the Right Reverend the Prelates of England and Wales on the Subject of the Slave Trade. Furthermore, by 1792 abstention had really come into its own as an abolitionist tactic. In 1791, William Fox, a Baptist, had published An Address to the People of Great Britain on the Propriety of Abstaining from West Indian Sugar and Rum. Other pamphlets advocating abstention were published or reprinted in Dublin in 1792. Thousands gave up sugar in their tea and boycotted other slave-produced goods, including people Mary knew in Ireland. One original contribution of her poem is the way she appeals to women's sense of solidarity as 'sisters', utilising the contemporary construction of 'woman' as the tender sex to argue that this sensibility, far from excusing inaction, entails greater responsibility. Women are not innocent or powerless - they have an 'important share' in causing slaves' suffering through their own consumption, and power to effect change by refusing slave-produced goods and influencing their menfolk to do the same.

Later in the 1790s, Mary's ideas on education, politics, and religion were much influenced by those of a Quaker schoolmaster and elder with some views tending toward rationalism and free thought. She does not name him, but it is virtually certain he was Abraham Shackleton, headmaster of a well-known school at Ballitore, which Edmund Burke had attended, forming a lifelong friendship with Abraham's father, Richard. Abraham Shackleton became a key figure in a bitter controversy, initially about the authority of scripture, which divided conservative and evangelical Quakers in Ireland from those of a more liberal or radical persuasion. Encouraged by her mentor, Mary immersed herself in the works of Jean-Jacques Rousseau, the French philosophes, and the radical Thomas Paine, but later recanted beliefs she cast as 'deist' in 1798 in a narrative entitled 'Progress of Infidelity'.

In 1801, Mary married Nathaniel Card, a Dublin merchant. The couple had eight children, but lost four in infancy. Mary was deeply affected by these deaths. Sadly, she believed a child's illness or death could be punishment for her sin: sometimes the 'sin' of opposing the will of her husband, or other 'sins' in speech that transgressed traditional gender boundaries. This rather challenges feminist assumptions about the relative autonomy of Quaker women. After 1804, she turned increasingly from poetry to religious prose. The Cards frequently experienced financial difficulties, becoming almost bankrupt on at least one occasion, and money worries permeate Mary's journal. Despite these problems, she led a full life, combining domesticity and helping in the family business with philanthropic work, for example in charity schools, and activity in the Quaker organisation. She was closely involved in the life of the Society of Friends. She took on several offices, becoming Clerk to Dublin Meeting of Women Friends from 1813-1816. In 1807 she published a poem on the death of Joseph Williams, a revered Quaker elder. And her interest in antislavery continued. In 1806 she addressed a poem to Hans Hamilton, a Member of Parliament for Dublin County, urging him to support that year's anti-slave trade bill. This was probably her response to the London Abolition Committee's recommendation, in March 1806, that individuals write to their MPs. Thomas Clarkson was asked to make Irish abolitionists aware of this tactic (Jennings, pp.105-06).

Unfortunately, Mary did not enjoy good health in her later years; her journal speaks of a liver complaint. She died in 1817 after an illness which The Annual Monitor, a Quaker obituary publication, describes as 'apoplectic'.

© Josephine Teakle 2006

E-mail: j.teakle@btopenworld.com

Bibliography

Works

Works Transcribed from Manuscript and Biography

Works in Facsimile

Secondary Works

For information on George Harrison and his abolition work, see:

Links

The Contributor

Josephine Teakle completed her PhD at the University of Gloucestershire in 2004. She is the great-great-great-granddaughter of Mary Birkett Card.