Thomas Day (1748-1789)

Biography

For most of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries Thomas Day was remembered only as the author of Sandford and Merton, one of the earliest novels intentionally written for children, but during his lifetime he was equally known as a philanthropist, poet, and political essayist. Although he died early on in the abolition campaign, he nonetheless contributed to it three important texts, including the first poem to directly attack slavery.Day was born in London and as a child was said to have been exceptionally kind to animals, and generous to the poor. As a student at Oxford University, he came under the influence of Jean-Jacques Rousseau. He became close friends with Richard Lovell Edgeworth (the father of Maria Edgeworth) who shared his enthusiasm for Rousseau's educational theories, and in a famous and eccentric experiment, Day decided to educate two orphan girls on Rousseau's principles in the hope that one of them would make him a suitable wife. Predictably, the experiment failed. The girls, by now young women, were given allowances to enable them to live a comfortable existance. One of the two later married Day's friend John Bicknell.

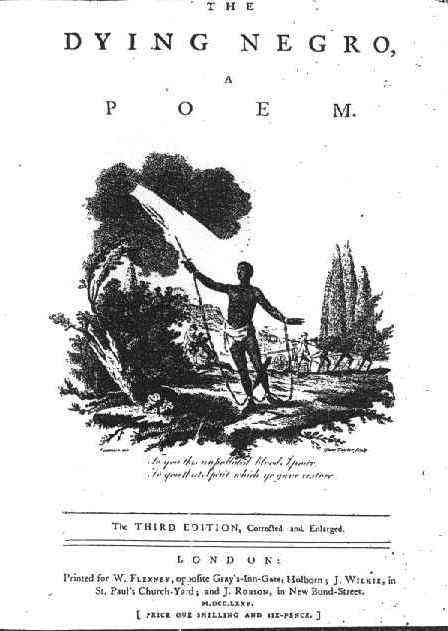

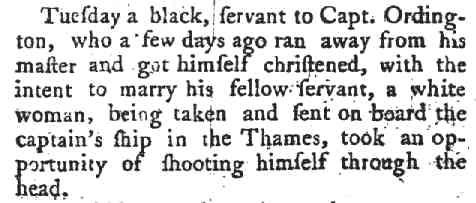

In 1773, Day moved to London to study law (which he never practiced). In May, a newspaper article about a slave who had committed suicide rather than be sent to labour in the plantations so horrified Day and Bicknell that they quickly wrote and published The Dying Negro. The poem was one of the earliest direct literary attacks on slavery and the slave trade, and can be seen, in part, as a response to the lukewarm enforcement of the famous Mansfield decision of the previous year. Lord Mansfield, in a case brought by the abolitionist Granville Sharp, had ruled that no slave could be compelled to leave the country against his or her own will - precisely the fate awaiting the slave who inspired the poem. The poem itself is long, influenced by the polite genre of sensibility, but also representing Africans as noble savages, uncorrupted by the "sordid gold" of "Christian traffic". These themes are united early on in the poem when Day argues that:

In their veins the tide of honour rolls;In fact, the poem is a suicide note in verse which alternately considers the dying slave's feelings, and the system that led him to suicide. To illustrate the latter, the poem outlines some hard facts about the lives of plantation slaves, slaves who;

And valour kindles there the hero's flame,

Contempt of death, and thirst of martial fame:

And pity melts the sympathising breast.

Rouz'd by the lash, go forth their chearless wayThe horrors of the plantation, and the treacherous manner in which the Dying Negro was abducted from Africa, are told at some length before being contrasted with the domestic tranquility he found in England. The way in which he won the love of the servant girl he planned to marry is told in strongly sentimental terms:

And while their souls with shame and anguish burn,

Salute with groans unwelcome morn's return.

Still as I told the story of my woes,This heart-warming domestic scene does not last long. The poem concludes with an angry passage in which the dying slave prays despairingly to the God to whom, with his baptism, he had recently turned. Like Christ himself the slave asks God why he appears to have forsaken him: 'when crimes like these thy injur'd pow'r prophane, / O God of Nature! art thou called in vain?' The closing lines of the poem contain a call for revenge, and with his dying breath the poem's narrator asks God to arrange that the slave ship on which he has committed suicide will sink, and all its crew will drown. In that moment, he hopes, the slavers' prayers will also go unanswered - the final couplet of the poem asks that; 'while they spread their sinking arms to thee, / then let their fainting souls remember me!'

With heaving sighs thy lovely bosom rose;

The trick'ling drops of liquid chrystal stole

Down thy fair cheek, and mark'd thy pitying soul;

The poem was extremely successful, and a second edition appeared in 1774. This edition was expanded and revised, and contained an essay opposing slavery, formally dedicated to the philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau. The essay contains an attack, among the first of its kind, on the hypocrisy of the British colonists in America. Day argues that it is for the benefit of the American colonists that 'the Negro is dragged from his cottage, and his plantane shade' and that thus 'the rights of nature are invaded'. He then emphasises the hypocrisy: 'yet such is the inconsistency of mankind!' he argues, that 'these are the men whose clamours for liberty and independence are heard across the Atlantic Ocean'. As long as the colonists keep slaves, Day argues, these are "wild inconsistent claims". Very early on in the American Revolution, two years before the Declaration of Independence, Day is already making a case that was to be restated by abolitionists on both sides of the Atlantic right up until the thirteenth amendment was passed in 1865. The poem continued to be popular, and a third edition was issued in 1775. This was further expanded, and is now the definitive edition. Reprints of the poem continued to appear into the nineteenth century.

Day's next attempts at poetry took the side of the American colonists and, for this reason, were less popular. In The Devoted Legions (1776) and The Desolation of America (1777) he drew a gruesome portrait of the despoliation of America by British and Hanoverian troops, concluding that "o'er the wasted fields and dreary plains, / In silent horror desolation reigns." During this period, Day met Esther Milnes, who admired and, more to the point, was prepared to tolerate Day's principles. They were married in August 1778. They lived a spartan lifestyle, observing Day's principle that "we have no right to luxuries while the poor want bread." During the crisis of 1780, Day involved himself with radical politics, as both a propagandist and public speaker. At the general election, he was urged to stand, but declined to join the "tribe of begging, cringing, shuffling, intriguing candidates". He dropped out of politics, and retired to his country estate in Surrey.

Here he wrote The History of Sandford and Merton (1783), a novel inspired by Richard Edgeworth's complaint that there was no suitable reading for his children. It contains an anti-slavery message from the start. Young Tommy Merton, the child of a rich Jamaica plantation owner, has been badly spoiled by life in a corrupt slave-owning society, where his every whim is catered for by an army of domestic slaves. Tommy is sent to England to receive an education, and there he becomes friends with Harry Sandford, the virtuous and self-reliant son of a "plain, honest farmer". The local clergyman, Mr Barlow, becomes the boys' mentor and both Tommy and Harry are improved - Tommy more so. The work was extremely popular and in response Day produced two further volumes (1787 and 1789). In the 1789 volume he responded to the antislavery agitation that was then at its height by including an African character and an antislavery episode. Taken as a whole, the novel is one of the first substantial works for older children, and it remained popular for over a century.

Day was at this time also working on a serious political treatise opposing slavery. When this appeared in 1784, with the title A fragment of an original letter on the slavery of negroes, it was amongst the earliest documents of the abolition movement. It appears not to have had a wide readership at the time, but was reprinted, at the end of an editon of The Dying Negro, in 1793. Day produced other literature during the 1780s, including The History of Little Jack, another children's novel, but none matched the success of Sandford and Merton. In September 1789 he was thrown from an unbroken horse which he had attempted to train by kindness, a favourite theory of his, and he died a few hours later from his injuries. He is buried at Wargrave near Henley-on-Thames, Oxfordshire. Though never playing an active role within the abolition committee, his contribution to the movement was nonetheless a significant one, not least in that dozens of poems, broadly imitative of The Dying Negro, appeared in the 1780s and 1790s.

© Brycchan Carey 2001-2015

Bibliography

Selected Works

- The Dying Negro A Poetical Epistle, Supposed to be written by a Black (Who lately shot himself on board a vessel in the river Thames;) to his intended Wife (London: W. Flexney, 1773)

- The Dying Negro: A Poem, 3rd edn (London: W. Flexney, 1775) | Read the full text

- Sandford and Merton: a Work Intended for the Use of Children (London: J. Stockdale, 1783-1789)

- Fragment of an original letter on the slavery of negroes (London: John Stockdale, 1784)

- Kitson, Peter, et al, eds, Slavery, Abolition and Emancipation: Writings in the British Romantic Period (London: Pickering and Chatto, 1999), 8 vols. The 1773 Dying Negro is in volume 4, while slavery-related extracts from Sandford and Merton are in volume 6.

Secondary Works

- Carey, Brycchan, British Abolitionism and the Rhetoric of Sensibility: Writing, Sentiment,and Slavery, 1760-1807 (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 2005). Day is discussed at pages 68-72 and 75-84. | More Information

- Carey, Brycchan, 'Abolishing Cruelty: The Concurrent Growth of Antislavery and Animal Welfare Sentiment in British and Colonial Literature', in The Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies, 43:2 (June 2020): 203-220. DOI: 10.1111/1754-0208.12686. Examines the bull-baiting episodes in Day's Sandford and Merton.

- Gignilliat, George Warren, The Author of Sandford and Merton: A Life of Thomas Day, Esq (New York: Columbia University Studies in English and Comparative Literature, 1931)

- Moore, Wendy, How to Create the Perfect Wife: Britain's Most Ineligible Bachelor and His Enlightened Quest to Train the Ideal Mate (London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 2013). Very readable popular history approach to Day's life, especially his attempt to educate two orphan girls. | View this title on Amazon

- Rowland, Peter, The Life and Times of Thomas Day, 1748-1789: English Philanthropist and Author; Virtue Almost Personified, Studies in British History, vol 39 (Lewistown, Queenston, and Lampeter: The Edwin Mellon Press, 1996)

- Snyder, Terri, The Power to Die: Slavery and Suicide in British North America (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015). Chapter Six contains a long discussion of The Dying Negro. | View this title on Amazon

- Uglow, Jenny, The Lunar Men (London: Faber and Faber, 2002). Day is one of the several members of the Lunar Society discussed in this entertaining and erudite work. | View this title on Amazon

Links

- On this website: The full text of the 1775 Dying Negro

Portrait of Thomas Day by Joseph Wright of Derby, oil on canvas, 1770.

The newspaper report that prompted Day and Bicknell to write The Dying Negro. The report appeared in at least three newspapers: The Morning Chronicle and London Advertiser, 253 (28 May 1773), The General Evening Post, 6181 (25-27 May 1773), and Lloyd's Evening Post (26-28 May 1773).

Title page of the third and fullest edition of The Dying Negro.